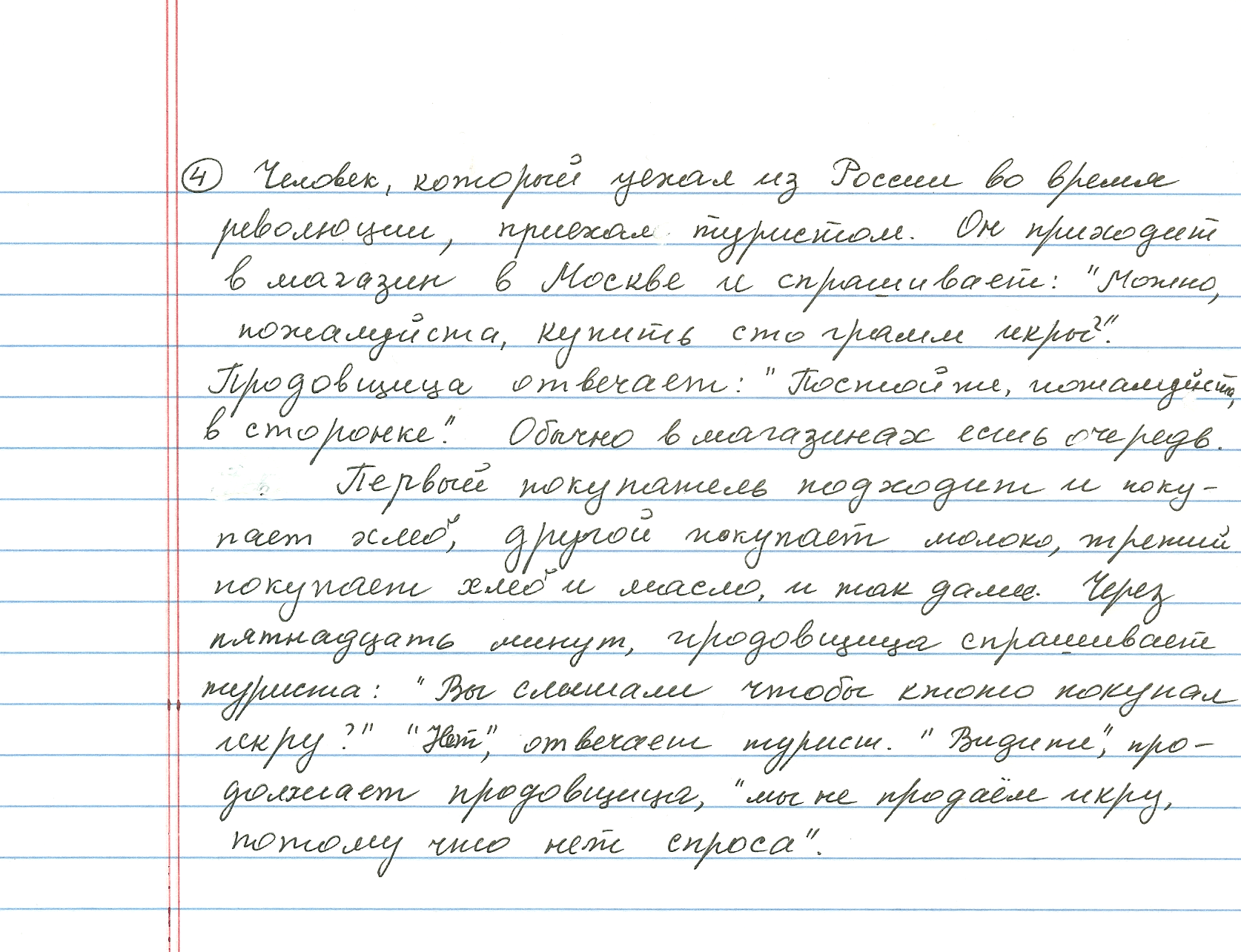

“A person who left Russia during Revolution came to visit. He comes to the store in Moscow and says, ‘Can I please buy a hundred grams of caviar?’ Well, there was no caviar in Soviet stores, it disappeared when I was a child, somewhere in the 1960s. I still remember when I was very little and my mom would take us to buy a little bit of caviar, and there would be black caviar and red caviar, and even though red caviar is considered to be the most expensive one, I liked the black caviar. And then, it disappeared because Russians suddenly realized—the Soviet authorities—that they can sell it for dollars, for foreign currency. So all of it went abroad and it disappeared in the Soviet Union. So that’s what you have to know before you can understand this joke. So the person comes and he goes into the shop and he says, ‘Can I buy a hundred grams of caviar?’ And the saleslady says, ‘Could you step aside, sir? Just stand here.’ There’s a big line of people, and one person comes and buys bread, and another person comes and buys milk, and a third person comes and buys something else, butter or bread. So, after the man stays there for fifteen minutes, she says, ‘Do you see anyone asking for caviar?’ He said ‘No.’ She says, ‘You see? We don’t carry it anymore because there is no demand for caviar.’

Link to Russian transcription of joke:

Q. What message is this joke trying to convey?

A. This is a joke about the shortage of food in the Soviet Union. It’s also about how the Soviet authorities would cover up the truth. Why we don’t have caviar? Not because there is no caviar in Russia, but because there is no demand. We always have some sort of an explanation. For example, at some point, in Lithuania, where I grew up, the Soviet Union started to take meat and send it to other parts of the Soviet Union, and also to Vietnam. And to cover up the shortage, they said that there is no demand for meat all the way through the week, and there should be a couple of days per week when the meat stores should be closed. (There were separate meat stores.) So, suddenly the meat stores are closed on a number of days. Why? Well, the truth is that there is not enough meat. What is the Soviet explanation? That people come from White Russia, from Belarus, which is a neighboring Soviet republic which really doesn’t have meat at all, come to Vilnius [the capital of Lithuania] and they buy all the meat. So, we don’t want to have meat stores open on the days that they come, like weekends.

Background on Soviet Jokes:

Q. Are these jokes that people would tell all the time?

A. Well, I remember them now, and I’ve been out of the Soviet Union for over thirty years. I knew them all my life. People would just sit down and they tell jokes, and if you have a new joke, that’s great. People learn those jokes, and they retell those jokes—it’s an underground joke industry. I don’t know how Soviet jokes originated, but all these jokes are something I grew up with, and thirty years later, I still remember them.

Analysis of Soviet Jokes: The Soviet regime was very oppressive. People constantly heard rhetoric about the greatness of the Soviet Union, and that it is a worker’s paradise, but in reality, the situation just grew worse and worse, and life only became bleaker. Thus, these jokes expose the population’s horrible disappointment in the regime. When I asked my informant whether people were idealistic about Communism in its early days, she told me that her grandparents were extremely idealistic about socialism, and believed that the Soviet Union would eventually become a great country with a high standard of living. When part of her family emigrated from Russia to Palestine in 1919, they invited her grandparents—and their children, of course—to come with them. But her grandparents declined, believing that socialist Russia would be a wonderful country. My informant’s parents grew up within this idealistic climate; in the 1930s, even though Russians experienced a horrible food shortage, people believed that since they inherited a terrible economy from the tsar, World War I, and the Revolution, the situation would eventually improve.

In contrast, by the time that my informant grew up, in the 1970s, the Soviet Union was corrupt through-and-through, and no one believed that there would be any improvement. In these jokes, then, we see people’s horrible disappointment, their cynicism, and their lack of hope for the future. The jokes never call you to resist the regime because resistance is futile and people feel powerless to change the system; rather, these jokes simply give people the satisfaction of laughing at the regime, an outlet for their disillusionment.