The informant is a 23 year old female, originally from Salt Lake City, who recently was a Peace Corps volunteer in the city of Guayaquil in Ecuador. While in Ecuador she lived with a host family and observed and participated in many Ecuadorian customs. One custom she was taught and picked up was the custom of re-purposing old chip, ice cream and other wrappers to make colorful pouches and purses. She describes her experiences and this folk craft below.

“There’s a strong tradition in Ecuador at least, and I’ve been told in many South American cultures, of doing what is known as “Microempresas” which is a small business – like a cottage industry essentially. Women especially will make things in their home out of every day objects or easily obtainable objects and resell them within their communities in order to make extra money. One such activity that I was taught was in making purses and coinpurses up to the size of handbags out of recycled plastic – durable plastic bags such as chip bags or a thicker plastic wrapping that’s easily tearable. And it’s appealing because you know people eat chips and have ice creams, things like that on a regular basis and it’s [the wrapper] something that would typically be discarded, and yet you can arrange the colors in different patterns. Because it’s individual folds that are then folded together in a chain it’s variable in its patterns and colors. And then sown together with wire or a fishing line or something that is also potentially a discarded object in order to make a pouch – and waterproof. I guess the cool thing about that too is that it also gives an opportunity for people to pass that down within their communities as well as to other people. An easily translatable skill that people tend to get together and do as a community rather than something more self producing. ”

When queried, the informant gave more information about what kind of environment she made pouches in when she was living in Ecuador:

“I would make them solitarily just because it’s something that you can do with your hands while you’re watching TV or something – like knitting. But people also would get together and you know trade bags and do it as a community effort.”

Information on process:

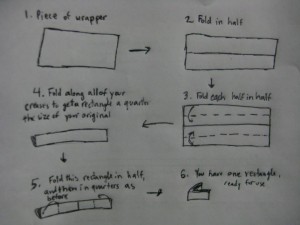

The first step of the process is cutting or tearing your plastic into usable rectangles. The size of the rectangles is different depending on how big you want each individual stitch of the ‘weave’ to be.

The steps to transform this rectangle into a usable rectangle that can be hooked with other rectangles created as shown below:

You then connect these rectangles together in a line to create loops one rectangle wide. You then sew all of these loops together, maybe add a zipper, to get you purse, pouch or coin purse

Image:

Analysis:

This folk object definitely serves a useful function. It is waterproof, looks interesting and the folk method used can produce a variety of different sizes and styles of objects. The making of a these folk objects seems to build community and unity in two ways. Firstly, the producers often gather together as a community to make these pouches. Secondly, it fosters a care for the place they live in a it uses trash that otherwise might have been put into the dump or littered on the streets. They are both building personal community while protecting/keeping clean their surroundings and environment.

The creation of this folk object is similar in many ways to a type of bracelet it was popular to make when I was young. I used the same folding method when I was a kid to make bracelets out of Starburst wrappers. I never sewed any of them together, but both folk objects are similar in their use of bright candy wrappers and the way they are folded. I had never made or seen a pouch made from this method until shown this folk object.