The summer camp councilor describes the legend of the Drop Bears at Camp Orkila, a traditional overnight summer camp on Orcus Island, WA.

When I was in middle school I went to Camp Orkila three summers. And the second time I was there, we had this councilor called Jim who had me completely convinced that drop bears are real.

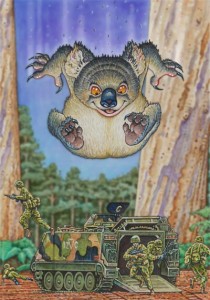

Drop bears are a dangerous cousin of the koala bear. Jim described them as looking like koalas except with razor-sharp teeth. They live in trees and at night they drop onto your head, knocking up unconscious. Then they eat you. And he wore this skate helmet at night for protection. He warned us not to leave the cabins at night without a flashlight and he said even with a flashlight we still might be eaten.

The source explained that the story was that the bears had been brought to the island by the Seattle Zoo in the 1930s after the zoo couldn’t contain them. The helmet is what convinced the source that the councilor wasn’t lying. After all, why would he bring a helmet and wear it every night if the threat wasn’t real.

All the other boys in our cabin didn’t believe Jim at all. They knew he was B.S.ing them but I totally bought it and I was really convinced and I would argue with them about it.

Well long story short, last summer I was the lead Grey Wolves councilor at Orkila—councilor for boys aged ten to thirteen—and I brought my bicycle helmet and I told them all about drop bears.

Did they believe you?

[laughs] Well… they said that they did not but I know I scared some of them.

From internet research, it’s clear that drop bears are usually are typically an Australian story. Typically, Australians tell foreigners about drop bears as a prank. The drop bears at Camp Orkila function exactly the same way. The camp councilors and experienced campers are in on the joke and they try to trick newcomers. Because original camp councilor brought a helmet with him a prop, it’s possible that he heard about drop bears on the internet or elsewhere and planned to bring it to Camp Orikila. The camp is an ideal place to spread folklore of this kind because the campers are away from home in an unfamiliar place without access to cell service or the internet, making them much more likely to believe. As with other pranks, the drop bears story at Orkila can also serve as an initiation, or a mild hazing of newcomers.

https://australianmuseum.net.au/drop-bear